A Study of Artist Aaron Douglas: Painting the Human Figure in the Tradition of Resistance

Lesson by Patty Bode and Stephanie Schmidt

In this lesson, students will learn about Aaron Douglas and draw silhouettes of marchers, cut out the figures, and paint in Aaron Douglas’s style. See also related art lessons Remembering the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike: A Collaborative Mural and Marching for Civil Rights Today: A Collaborative Mural.

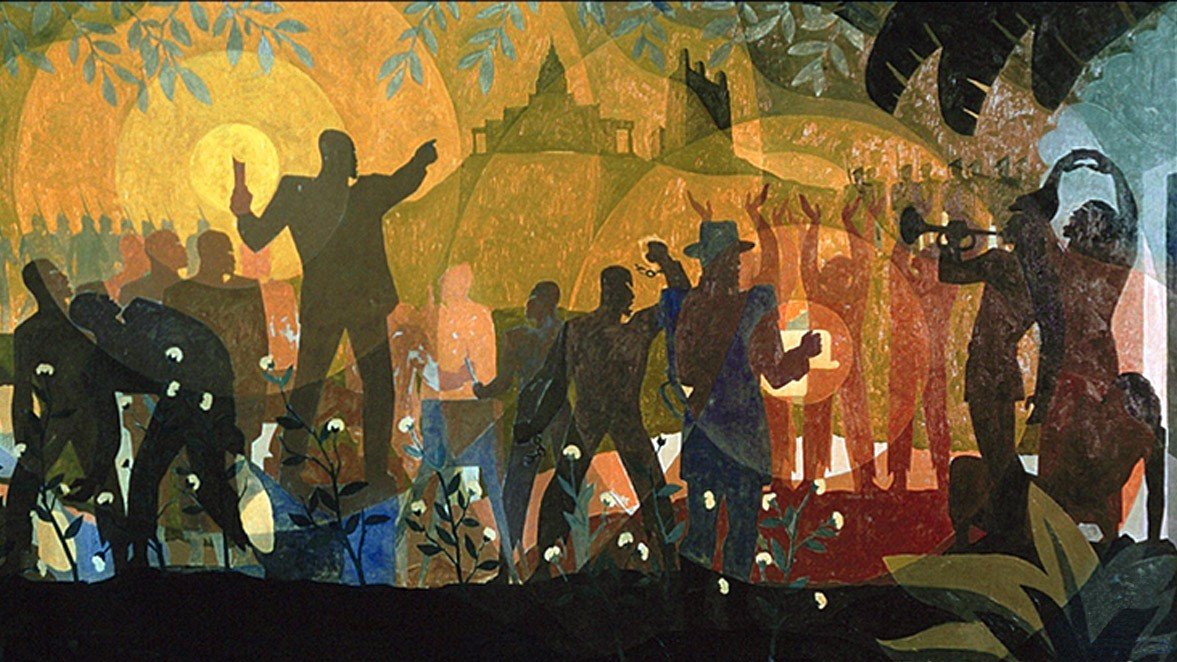

Aaron Douglas, Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction. New York Public Library.

Providing students with an artist mentor is inspiring and motivating. The artwork and leadership of Aaron Douglas foreshadowed the Civil Rights era by setting the visual tone of the Harlem Renaissance movement of the 1920s and 1930s. Aaron Douglas was a leader in the Harlem Renaissance school of painting, and one of the first artists to document the history of the African-American experience through visual art.

His style was innovative and intriguing and is still viewed as a powerful expression of the oppression and resistance of African Americans. He was an artist who pushed the boundaries established by previous artists, creating portrayals of the African American experience that recognized its history and its African roots. In his 1936 painting, Into Bondage, Douglas depicts the perspective of the enslaved— African people in their native land chained and walking in a line to their horrifying fate. More prevalent in Douglas’s work, however, were images of empowered African Americans. This innovation can be seen in many works, such as Study for God’s Trombones (1926). Douglas portrays the harsh reality of slavery in this image, but depicts the person breaking free from the chains. His piece Building More Stately Mansions (1944) shows the achievements of African Americans throughout time by blending images from ancient Egypt and contemporary New York, while Aspirations (1936) contains symbols of musical accomplishment and achievement in scholarship and business. Although his work actually preceded the Civil Rights Movement, it is such a strong example of art documenting historical achievement and resistance that it makes sense as a place to start this lesson. Douglas was a well-established muralist and painter who regularly contributed illustrations and designs to publications including Opportunity, The Crisis, Theater Arts, American Mercury, and Vanity Fair.

Called the “Father of African-American Art,” Douglas founded the art department at Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee. He was also a social activist whose best-known mural series, Aspects of Negro Life (1934), was commissioned by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration and is displayed at the Countee Cullen Branch of the New York Public Library. Douglas was also the first president of the Harlem Artists Guild (1935). His contributions have had a lasting influence on the art world and are a testament to African-American history and pride. When students learn about such expression in the context of the art history of the 1920s and 1930s, it sets the stage for the study of the Civil Rights Movement.

Objectives

Aaron Douglas. Image: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

To learn about the historical context of Douglas’s work

To understand Douglas’s creative expression and art techniques

To introduce painting’s color theory of tints and shades

To study the human figure through gesture and design

To create a painted cut-out of a civil rights marcher that will later be applied to a mural that the whole class will complete

Guiding Questions

What do we know about the Harlem Renaissance?

What do you notice in the Aaron Douglas paintings?

What do you see in the paintings that you wonder about?

How does Aaron Douglas give strength and character to his figures, despite the fact that they are silhouettes?

How does Douglas use color in his paintings?

What effect do the concentric circles and geometric lines that cut through

the picture plane have on the image?

How does he balance realism with abstraction?

What stories do these images tell?

Materials

Flip chart

Video: Against the Odds: The Artists of the Harlem Renaissance

Examples of Aaron Douglas paintings (see Resources at the end of this article)

Pencils

Scissors

12” x 18” white oak tag

Compasses

Circle templates of various sizes (plastic lids are good for this, or you can make some out of oak tag)

Tempera or acrylic paints

Paintbrushes

Mixing trays (empty cups or egg cartons for mixing paints)

Plastic spoons

Procedure

Class Discussion and Motivation

Start class discussion with the first guiding question: What do we know about the Harlem Renaissance? Make a list of student responses on large flip-chart paper. This both affirms their knowledge, as well as their questions, and also works as a kind of teacher’s guide to check for any missing information that requires teacher and students to do further research.

Many children have not learned about the Harlem Renaissance in school, so this lesson provides an opportunity to develop knowledge about the era’s rich artistic expression and the social and political forces that propelled the African-American community to create the Harlem Renaissance movement. I always ask students to recall what information they have previously learned in school and in textbooks about United States history during this period and to think about the reasons that information about the Harlem Renaissance was omitted from that curriculum. I use this social context to help students understand that the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s did not spring up in a vacuum.

View the video Against the Odds: The Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. This program provides the sociopolitical context of the Harlem Renaissance and emphasizes visual images of African Americans. It demonstrates the way visual culture colludes with political forces in acts of oppression and resistance. Various artists are discussed. Since the running time of the video is 60 minutes, teachers may want to choose excerpts to make the points they want to emphasize or clarify and to capture the attention of their students, depending on their developmental level.

After viewing the video, look closely at some of the paintings by Aaron Douglas in the books listed at the end of this lesson under Resources. Ask students, “What do you notice? What do you wonder about?” These two questions elicit open-ended responses from the most reluctant participants as well as the most vocal:

They will notice figures walking away from an African landscape toward a ship.

“Maybe it is a slave-trader’s ship.”

They will notice images of magnificent engineering feats collaged into one scene: Egyptian pyramids, the Brooklyn Bridge, skyscrapers.

“Maybe Mr. Douglas is showing all the work of African-American people throughout history.”

They will notice that streams of light direct the viewer’s eye in each painting.

“I wonder if that beam of light is the ray of hope for African Americans.”

“I noticed that he always shows people looking up and forward.”

“I wonder why he uses those circles going around and around in every painting?”

Aaron Douglas, Aspects of Negro Life: The Negro in an African Setting. New York Public Library

Then move on to the other guiding questions. By the end of the discussion, the class will have made a very sophisticated analysis of the paintings.

After listing students’ comments on the flip-chart paper, discuss the goal of making a mural. Teachers may choose one of the mural projects described in Remembering the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike or Marching for Our Own Civil Rights, or develop a longer unit of study to do both murals.

Overview and Technique

For this activity, students will draw silhouettes of marchers, cut out the figures, and paint in Aaron Douglas’s style.

First students will observe each other walking. Then they will pose for each other in positions that would be made by protesters. Observe the bends in legs and arms as well as body proportions. If available, refer to a simple picture that illustrates human body proportions. Suggest that students consider what it looks like when someone holds a protest sign, steps with pride, and expresses strong resistance. While doing this, talk about gesture. Show students how gestures affect their thinking and reactions. Ask them to notice the difference in ability to communicate when they use strong or many gestures and when they use weak or no gestures. Explain to students that they will be making silhouettes of their figures, so their depiction of character relies on the gesture, or stance, of the figure, not facial expressions or clothing.

Students must decide on a gesture, or position, for their protester. Ask them to consider what they think would be more effective: drawing their figure from the side or from a frontal point of view. Have each student use a pencil to draw the outline of a person in a protest. Demonstrate that by drawing lightly and using basic shapes, students can make their figure by first drawing all body parts and then going over the outline with darker lines. It would probably be more difficult to draw only the outline of the body.

After drawing their figure, students then use scissors to cut it out.

Next, study Douglas’s use of design. The concentric circle and linear designs he uses cut through the picture plane and add depth to his otherwise flat images. To replicate this technique, students can use circle templates and/or compasses. Remind them to draw lightly with their pencils, so their lines do not show dramatically on their final piece. Also, point out that parts of their circle or lines may be visible on the figure, then “disappear” off the edge of the figure and then reappear on the figure. For example, as one draws a large circle, it may be drawn on a leg, then go off the figure in the negative, or empty, space surrounding the figure, then reappear on a hand or arm. It is advisable for each student to draw at least four circles inside each other to have a repeated concentric affect. You may want to specify the number of lines or circles they must make depending on their age. Setting a maximum limit also ensures that a student will not have too many shapes to paint inside. Remember that it is easier to start with a larger circle, and then to trace a smaller circle inside it so that it can be centered inside the first one. If you start little, a bigger template will cover the drawn image, making it difficult to center the images.

Discuss Douglas’s use of limited color. Introduce the terms tint and shade. Explained simply, a tint is a color with white added to it, and a shade is a color with black or brown added to it. Students must choose a color to paint their figure and make different tints and shades of that color by adding varying amounts of black and white. (Egg cartons are useful for mixing: put some white in the last few egg cups, some black in the other end of the egg cups, and your color of choice in the middle, while leaving a few egg cups available for mixing.) Consider whether you want the colors of the figures to be similar to or different from the mural background. This is a good opportunity for the group to share the varying tints and shades they have mixed, so that everyone’s pieces connect nicely in the final mural; it also reinforces the sense of collaboration.

Students then fill in each shape with different colors. Colors may be repeated. Make sure to offer both large and thin brushes so students can most effectively approach each different shape.

When all of the spaces are painted and the pieces are dry, each student has a figure that can be applied to a large mural, as described in lesson 2, Remembering the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike and in lesson 3, Marching for Civil Rights. Keep figures in a safe place until ready for this step.

Synthesize, Assess, Evaluate

Historical Concepts

What do we know about the Harlem Renaissance?

How did the artistic expression of the Harlem Renaissance foreshadow the social action of the Civil Rights Movement?

What do we know about Aaron Douglas? How did his leadership influence artists of the era and artists throughout the century?

Art Content

Did each child understand the concept of drawing a silhouette?

Did students strategically depict a gesture that gave their figure a sense of character or expression?

Does each figure show that students understand the concept of concentric circles?

Do the images have a balanced effect when grouped together?

Did students mix both tints and shades that varied in gradation?

Resources

Against the Odds: The Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Directed by Amber Edwards. 60 minutes. PBS Home Video, 1994. Provides an excellent overview of Harlem Renaissance and the artists involved; contains archival footage, interviews, more than 130 paintings.

Aaron Douglas: Art, Race, & the Harlem Renaissance by Amy Helene Kirschke gives a biography of Douglas and the sociopolitical context of Harlem Renaissance. Includes several black-and-white illustrations.

Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America by Mary Schmidt Campbell provides essential text on many Harlem Renaissance artists, as well as photos and color art reproductions of their work.