My Students Convinced Me to Let Go of Old School Teaching

Teaching Reflection by Susan Nail

I had always been an “old school” teacher and believed in the traditional lecture/notes type of classroom. This is what I grew up in, this is what I knew: a quiet classroom with everyone on task, listening to a lecture or reading a textbook. As a new teacher, I found that breaking this cycle was a struggle. I watched as other teachers used interactive activities within their classrooms. It seemed that the students enjoyed that so much more, but was it worth it? Again, I grew up “old school” where education was concerned.

A few years ago, with the help of a few of my colleagues, I conducted my first real collaborative activity with my high school students. We were working on our civil rights unit. I wondered how I could help my students understand this important piece of history. I could talk to them all day long about what citizens experienced during the Civil Rights Movement based on what I had read, but how would that help them understand? My colleagues gave me some wonderful primary documents and activities. I reluctantly set out to use them with my high school students.

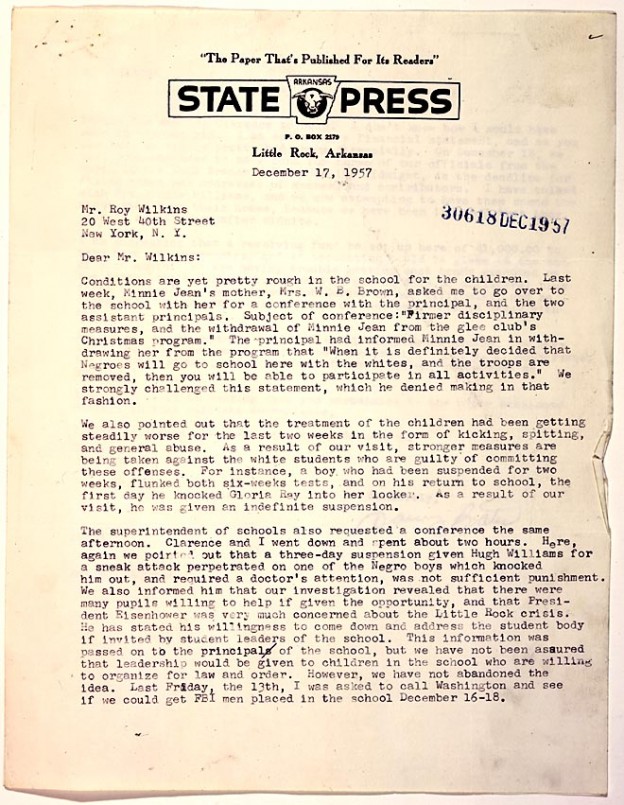

I started with a letter by one of the Little Rock Nine. I pulled archived news feeds from Little Rock and posted photos. I also pulled photos and documentary information on the Woolworth Sit-ins, both in Greensboro and in Jackson, along with other archival photos and documents, such as the Jim Crow laws. I had my students analyze and write about the materials. They really had to think deeply and they had to infer how it made the parties involved feel.

As they rotated, read their materials, discussed, and wrote, I was still wondering if the traditional way of teaching wouldn’t be “better” and “easier.” Were they really learning anything? Would they remember the insights from this lesson? Some seemed excited about trying something new, some complained about the writing aspect (as many of them always do), and some just seemed indifferent. (Notice, I said “seemed.”)

As they worked within their small groups and I began to rotate and listen, I was amazed at the conversations that were taking place. Comments like “no way that happened, dude,” “that’s just janked up,” “did all this really happen or is Mrs. Nail pulling a good one on us?” At the same time, I noticed the emotion that was surfacing.

John Salter, Joan Trumpauer, and Anne Moody sit-in at the downtown Woolworth’s in Jackson, Mississippi, on May 28, 1963. They are surrounded by a mob who pour ketchup, sugar, and other condiments on them. Source: Fred Blackwell, Erle E. Johnston Papers, University of Southern Mississippi Libraries

The lesson took a couple of days. When we wrapped up our group collaboration and came back together for whole group discussion, I really saw the magic begin to happen. For the first time in a while, their chatter was about historical content. Sheer amazement and disbelief was their response to some of the things they had learned. As the discussion went, I found that I just had to clarify misconceptions and answer a few stray questions or simply redirect the discussions, some of which became heated.

This was toward the end of the year and we were wrapping up trying to start to prepare for our final exams. It wasn’t until the beginning of the following year that I realized that what I had done really sank in. The students remembered the lesson and they were still excited about it. I was amazed at what they had retained.

From there my vision changed. Obviously I can’t do group work with every single lesson, but I have now seen the importance of it first-hand. I have incorporated more and more interactive work into my lessons, both individually and within groups. I am now convinced that my students learn more with me as more of a “facilitator” vs. being a “traditional” teacher. I look forward to many lessons that I dreaded in the past because I have come to realize the true impact of student exploration.

My advice to a new and upcoming teacher, who may be like my former self is to dive in head first. Yes, it takes a lot of initial work to prepare for these types of activities. The thing to remember is that there are so many veteran teachers, and even new teachers who are wonderfully creative and amazing at what they do, who are more than willing to share resources and lend assistance with this. In the end, the students do all of the work, you become a more effective “facilitator” to offer guidance. The lesson becomes relevant and meaningful to the students, and retention takes place. Embrace the challenge. ■

Susan Nail wrote this reflection while teaching at Kosciusko High School in Mississippi, and a 2015 Mississippi Civil Rights Movement and Labor History fellow with Teaching for Change. She has taught geography, Mississippi Studies, and World History.