Fists of Freedom: An Olympic Story Not Taught in School

Reading by Dave Zirin

The real story behind the most political, controversial, inspiring moment in Olympics, if not sports, history: the black gloved salute of runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos. To learn more about athlete protests, read “Athletes, Protest, and Patriotism” and follow Dave Zirin’s Edge of Sports column and podcast.

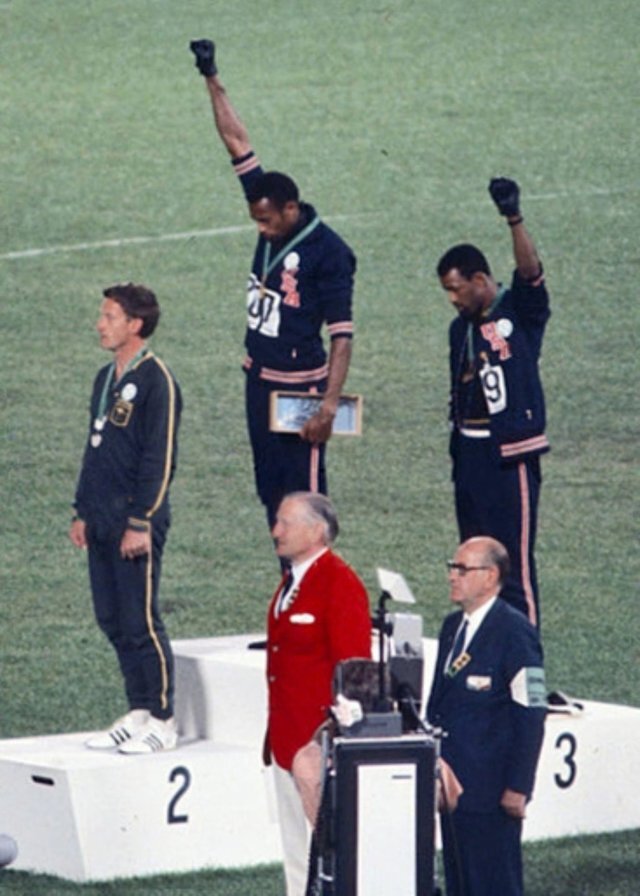

Gold medalist Tommie Smith and bronze medalist John Carlos showing the raised fist on the podium after the 200 m race at the 1968 Summer Olympics; both wear Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) badges. Silver medalist Peter Norman from Australia also wears an OPHR badge in solidarity with Smith and Carlos. By Angelo Cozzi (Mondadori Publishers).

It's been more than 50 years since Tommie Smith and John Carlos took the medal stand following the 200-meter dash at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City and created what must be considered the most enduring, riveting image in the history of either sports or protest. But while the image has stood the test of time, the struggle that led to that moment has been cast aside.

When mentioned at all in U.S. history textbooks, the famous photo appears with almost no context. For example, Pearson/Prentice Hall’s United States History places the photo opposite a short three-paragraph section, "Young Leaders Call for Black Power." The photo's caption says simply that "...U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised gloved fists in protest against discrimination."

The media — and school curricula — fail to address the context that produced Smith and Carlos's famous gesture of resistance: It was the product of what was called "The Revolt of the Black Athlete." Amateur Black athletes formed OPHR, the Olympic Project for Human Rights, to organize a Black boycott of the 1968 Olympic Games. OPHR, its lead organizer, Dr. Harry Edwards, and its primary athletic spokespeople, Smith and the 400-meter sprinter Lee Evans, were deeply influenced by the Black freedom struggle. Their goal was nothing less than to expose how the United States used Black athletes to project a lie about race relations both at home and internationally.

OPHR had four central demands: restore Muhammad Ali's heavyweight boxing title, remove Avery Brundage as head of the International Olympic Committee, hire more Black coaches, and disinvite South Africa and Rhodesia from the Olympics. Ali's belt had been taken by boxing's powers-that-be earlier in the year for his resistance to the Vietnam draft. By standing with Ali, OPHR was expressing its opposition to the war.

By calling for the hiring of more Black coaches as well as the ouster of Brundage, they were dragging out of the shadows a part of Olympic history those in power wanted to bury: Brundage was an anti-Semite and a white supremacist, best remembered today for sealing the deal on Hitler's hosting the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. By demanding the exclusion of South Africa and Rhodesia, they aimed to convey their internationalism and solidarity with the Black freedom struggles against apartheid in Africa.